There was this pig barn. It was 28 years old and no longer meeting expectations. The pigs were not thriving and, in May alone, its operators lost $22,000. The veterinarian had suggested shutting it down.

This is where some honest collaboration between the veterinarian and a nutrition specialist intervened to save the day.

At 7:30 on a muggy Friday morning, swine veterinarian Cordell Young from Lethbridge and agriculture supplier Harry Korthuis from High River meet over breakfast to talk about the plan they had created to save the barn. Korthuis is on his way for a follow-up visit and wants a debrief along with some of the data Young had collected to lay out for the barn manager so he could see the impact of the changes and upgrades that had pulled his business back from the precipice.

With their recommendation, the farm had upgraded its feeder facilities and added a scale to enable weekly weighing of the pigs. That gave the barn manager the information needed to monitor progress in the room and make the necessary adjustments.

Korthuis said he was also able to get them a “smokin’ deal” on some new flooring.

What a difference, says Young.

“We figured out what the cost difference is on that – it’s about $2 a kg at the end, and we typically say one kg at the end of the nursery is three kg in the end of the finisher. That turns into $30 a pig.”

This chapter reached a happy ending because the feed supplier and veterinarian have worked in partnership rather than contradicting or crossing each other up, says Korthuis.

“There’s not enough money in the pig to waste,” he said.

“We work for the customer. A lot of vets want to be nutritionists, and that doesn’t work. If there’s an issue and they ask us if it’s a vet question, we make sure they know that they better get hold of the vet. When there’s something going on in the barn, and we know that this is what it takes to improve it, I don’t pull no punches. We work close together.”

That level of collaboration is an absolute must, says Young. His morning had opened with a call from a nutritionist with concerns about a misdiagnosis in one of the barns he serves. It appears the barn manager had been treating unsuccessfully for a nutritional imbalance when there was likely an undiagnosed infection within the herd.

That situation underscores the need to get the right diagnosis the first time, because treating the wrong problem can get very expensive, says Young. A herd health veterinarian’s role is to assess the operation and help a producer create a healthy environment to get the best possible performance from the pigs without costly trade-offs.

As the breakfast bill is tallied and the dishes cleared from the table, Korthuis and Young make their way out to the parking lot, where they wrap up their discussion with a handshake before heading off in different directions.

Young is on his way to a consultation at a farm that has run into some problems, including circovirus and PRRS (porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome) infections.

On the way, he stops to pick up a box of doughnuts and to fuel his thirsty pickup truck before it burns up the last fumes in its tank.

The barn manager and his crew have their hands full with breeding, but he takes some time out to discuss the costs and impacts of various therapies needed to care for his herd.

Pigs in one of the newer rooms have started biting tails and the manager is at a loss to figure out what is aggravating them. The problem has not arisen among similar animals in an older and “crappier” area of the barn, he says.

Young advises that it can take up to nine weeks from the time an issue develops in the room until the tail biting starts. He and his customer talk about a variety of therapies, such as administering penicillin or additional vitamins. He agrees to order some penicillin for the farm and the manager later acquires a vitamin package through his nutritionist.

In a later conversation with Prairie Hog Country, Young says the farmer has used both therapies and the tail biting appears to be under control.

Dealing with PRRS and circovirus poses a different challenge. Young outlines the costs and efficacy of different vaccines, but lets the client weigh out the options for himself. Throughout their meeting, Young is careful to offer various approaches without pushing the producer onto any particular path.

He explains that, along with the cost difference between different vaccines, there is a trade-off in terms of the amount of protection each one offers versus the immediate impact it will have on the pigs. The more expensive vaccine will be more immediately effective, but it may also set the pigs back more than the less costly product. Young advises that any vaccine split into two doses and delivered two weeks apart will be more effective than giving it all in a single shot.

The producer is hesitant about splitting the dose because of the additional handling required and the additional risk of breaking needles.

Ultimately, he makes his decision and sets up his order.

Back in the truck Young explains that he prefers to give producers the information they need to make informed choices about what is best for their farm but has found some who demand to be told what they ought to do. He has been fired by farm managers who don’t want to make their own decisions.

It’s noon and Young has only a few minutes to get home, shower, and drive to Great Falls where he will pick up the woman who mended his broken heart and saved his career. He plans to take her back to Yorkton to meet his parents for the first time.

Young met Erika Neuendorf briefly in January while visiting his brother in Wisconsin. Neuendorf had come from Salt Lake City to visit with his sister-in-law’s sister and, although he agreed to include her on a social media list, he wasn’t interested in going any further. His relationship with his former girlfriend, whom he had hoped to marry, had ended when she answered God’s call to join the ministry.

Reflecting on their parting, he says her call to the ministry was as strong as his call to vet school.

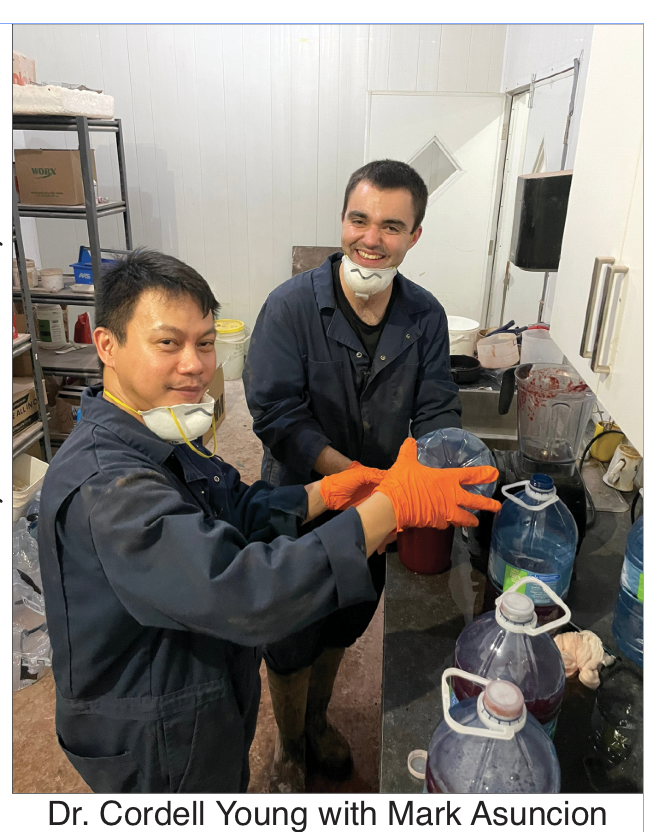

Young, now 30, had moved to Lethbridge in 2017, immediately after earning his degree from the Western College of Veterinary Medicine. He joined veterinarian Dawn Magrath in her practice, Innovative Veterinary Services, and two years later was recruited into the Quebec-based Demeter group of Canadian swine veterinarians. Its membership included veterinarian Kurt Preugschas, founder of Precision Veterinary Services in Red Deer. While remaining a Demeter member, Young eventually joined the Precision team, working out of Lethbridge with technician Mark Asuncion.

“I could not believe I’ve been blessed with as good of a partner as (Kurt). I just am in awe.

Kurt brings to our partnership an introverted, calculated and conscientious approach, where I am much more extroverted, blue sky, conceptual and people driven. He’s probably right-handed, I’m left-handed.”

The work is intense and the hours are long. By February of this year, Young was starting to burn out and he was questioning whether he could continue along his chosen path.

At the peak of his despondency, when he was considering leaving his career and accepting whatever fate awaited, Neuendorf called. She said she had felt strongly compelled to get in touch. They met, they started to date.

With Neuendorf’s support, Young burst out of his funk and regained his footing in his career with a new plan, including renewed dedication to developing his practice.

The work hasn’t gotten any easier and the hours are still long. During the second week in July, Young has put in 52 hours by Thursday afternoon and still has work to finish on Friday. Thursday was spent doing a Canadian Pork Excellence evaluation for a nearby farm. Heading back from the consultation on Friday, he refers to notes from the evaluation, written on both sides of a small sheet of paper, and dictates his findings – seven minutes worth – into his phone so they can be transcribed. Asuncion will format the transcript, and then return it to Young for his report.

Ultimately, all veterinarians are in the people business, although some people choose veterinary school because they don’t wish to deal with people, says Young.

He feels that trust and teamwork are essential and that one of the most important skills in his set is his ability to tease out the issues that his customer is not sharing with him.

“You know what you have to listen for? The things that they never tell you. And the things that they’re never going to tell you are, well, all of the details. They are never going to tell you their jobs to be done, and their jobs to be done always stand in the way between my recommendation and making progress. Understanding their jobs to be done and my jobs to be done in their situation is very complex. It’s a very complex picture.” •

— By Brenda Kossowan