He ambles through a deep pile of hay where his buddies are napping, looking for a little scratch. Shaggy red-brown hair masks his small, black eyes. A prominent row of lower incisors, yellowed and worn, is flanked between scimitar tusks. The nasty teeth, unruly hair and stubby snout give him a maddened grin akin to the face of Jabba the Hutt, lead gangster in George Lucas’s Star Wars fantasy films.

Regardless of his menacing appearance, Harlequin the Kunekune boar is truly a mellow fellow, sociable when people come to visit and well suited to pleasing his ladies at their home on Whispering Wind Farms, about 15 minutes straight west of Didsbury.

Pigs were not part of the plan when former Calgarians Jon Lendvoy and Kelly Worthington first moved onto an acreage closer to Carstairs. There was enough space on the property to run a few head of cattle, so Jon convinced Kelly that they should get some feeders and maybe supplement their income by marketing grass-fed beef.

Kelly wasn’t keen on cattle. While she had grown up in the city, she had belonged to a 4H horse club and had a passing familiarity with show cattle. Her most distinct memory of those beasts is that they would deposit a lot of crap. Everywhere.

However, she relented, and they picked up a few feeders which eventually evolved into a breeding operation focused on Galloway and Galloway-Angus crosses. Kelly says she soon had a change of heart about cattle and now loves her cows.

“I like all animals.”

While the beef proved popular, the couple had numerous inquiries about pork, specifically from people seeking pigs raised on pasture in the most natural environment possible. Jon wasn’t keen on the idea because he didn’t want pigs rooting up his pasture.

Watching an episode of The Incredible Dr. Pol piqued Kelly’s curiosity, when the clinic featured staff working with a Kunekune pig.

Then, in 2015, she learned on a shopping website that Ivanleigh Farms in Ontario’s Ottawa Valley had imported Kunekunes (pronounced cooney-cooney) and had some breeding stock for sale. This time, it was Jon who relented and agreed to the purchase.

“So, I contacted the breeder, put a deposit down and bought a breeding pair. I bought a boar from BC and a female from a breeder in Ontario. Then I found another breeding pair.”

While there is more mystery than fact surrounding the origins of Kunekune pigs, the existing stock traces to animals that were kept by indigenous people of New Zealand’s Māori Islands. There is speculation that the Māori developed their pigs from a mix of Asian and European animals dropped off by sailing ships during the 18th and 19th centuries. Various accounts state that it was common practice, especially among whalers and sealers, to leave pigs on the islands they encountered through their travels in hope that they would reproduce and provide a supply of fresh meat for shipwrecked or marooned crews.

Over time, and under care of their Māori keepers, Kunekunes developed some unique characteristics, including a short snout and heavy jowls that make them unable to root. The animals display a wide array of colours; they are heavy bodied, short legged and especially docile, producing a unique fat of exceptional quality.

“It melts in your mouth,” says Kelly.

“They are a lard breed, so you’ve got to be careful. You can get four inches of backfat on these guys if you’re not careful.”

She compares the fat to scallops for its density and lack of gristle, saying that it is especially attractive for charcuterie.

“We aim for about one and a half inches to two and a half (of backfat),” said Kelly. “We wanted to target the market that was more going toward healthy fats and looking for something that was raised outside.”

After getting their first breeding stock, she and Jon learned that efforts to rescue the breed from extinction had backfired in some respects.

New Zealand’s entire herd had shrunk to 80 breeding pairs when rare breeds conservators from the United Kingdom took a few home and started an aggressive program to build up their numbers. But the conservators were focused on preserving the breed without regard to breeding practices that would produce animals suitable for farm production. The result included numerous individuals with too much slope in their pasterns and with lightly boned legs that could not support their big bodies.

Jon and Kelly quickly learned to select individuals that would improve their genetics to correct the undesirable traits and focus on the physical and breeding characteristics that make Kunekune a desirable pasture pig with good growth traits, fertility and healthy litters.

Kelly and Jon rotate their gilts and sows over a nine-month breeding cycle, with three breeding periods per year. Sows farrow in large pens and breeding is coordinated so that for or five sows farrow and raise their piglets together. The piglets stay on the sows for 12 weeks, when they are naturally weaned.

Males selected for meat are castrated and run with the young females. Males and females of breeding quality may be sold to other producers who are interested in raising their own pigs. It is also not uncommon for rural families to buy barrows as a livestock project for their children. Others like to raise a few of their own pigs to feed their families and friends.

Kelly serves as an advisor and mentor for people who hope to raise their own pigs, ensuring that they are fully apprised of the importance of the biosecurity and traceability rules in force throughout the province and on her farm. All live animals that leave the farm are registered with Alberta Pork and Kelly strongly encourages those buying live animals for their own farms to keep the chain intact.

Working with veterinarian Jessica Law of Red Deer, she and Jon have developed a biosecurity protocol that includes boot washes or booties and hand sanitation for all visitors. The herd is closed to all outside pigs except occasional breeding stock from the Ontario farm that provided their first animals. People who already have their own pigs are not allowed on the farm and any pig that dies on the farm is necropsied to determine what caused its demise.

Food scraps are not used because of the danger that they may carry pathogens or other harmful ingredients, says Kelly. The “Kunes” thrive on a diet that is heavy in forage, supplemented with grain and distiller’s dried grains to ensure that they are getting adequate protein along with their mineral, says Jon.

Besides their inability to root, the Kunes tend not to challenge fencing and spend most of their day at rest.

“They’re quite a routine animal. They’ll have their breakfast, they’ll be up here for a little bit, and in about an hour they’re done for the day,” said Kelly.

Jon says the only animals that challenge their fencing are cycling females seeking attention from the boars, which are kept in a set of pens away from the sow herd and closer to the horses and the cows.

Like his buddies in the boar pen, Harlequin wears a plate of armour over his shoulders and ribs, where the skin is thick and calloused. Kelly says the natural armour helps protect the boars from bites. She and Jon don’t clip their teeth because, while the boars don’t fight most of the time, they will get a bit rowdy when one returns from the breeding shed. She has found that the few cuts from tusks are not as serious and heal more quickly than the muscular injuries that occurred when the boys did not have their tusks.

As their herd grew, Jon and Kelly started seeking a bigger property to expand their beef and pork herds. In January of 2022, they moved to their current site, a quarter section that had previously been operated as a horse farm, including pens, outbuildings and perimeter fencing. There are two hayfields where Jon raises an alfalfa mix for his animals.

He plans to divide the pasture into smaller paddocks and rotate his cows through them, with the pigs to follow behind. The pigs don’t do well on long-stemmed grasses, but forage nicely on shorter grasses and forbs, including thistles. Jon and Kelly plan to reseed the aged pastures, which had been badly damaged by years of grazing horses. They will include some brassicas in the seed mix specifically to enhance the pig diet. Kelly also hopes to plant a variety of fruit and berry trees to further augment the diet. She says it has become common in some areas of British Columbia to run pigs through orchards after the fruits have been harvested.

Perimeter fencing will be reinforced with page wire and it will be electrified to prevent incursions from outside animals, including feral pigs if they start moving closer.

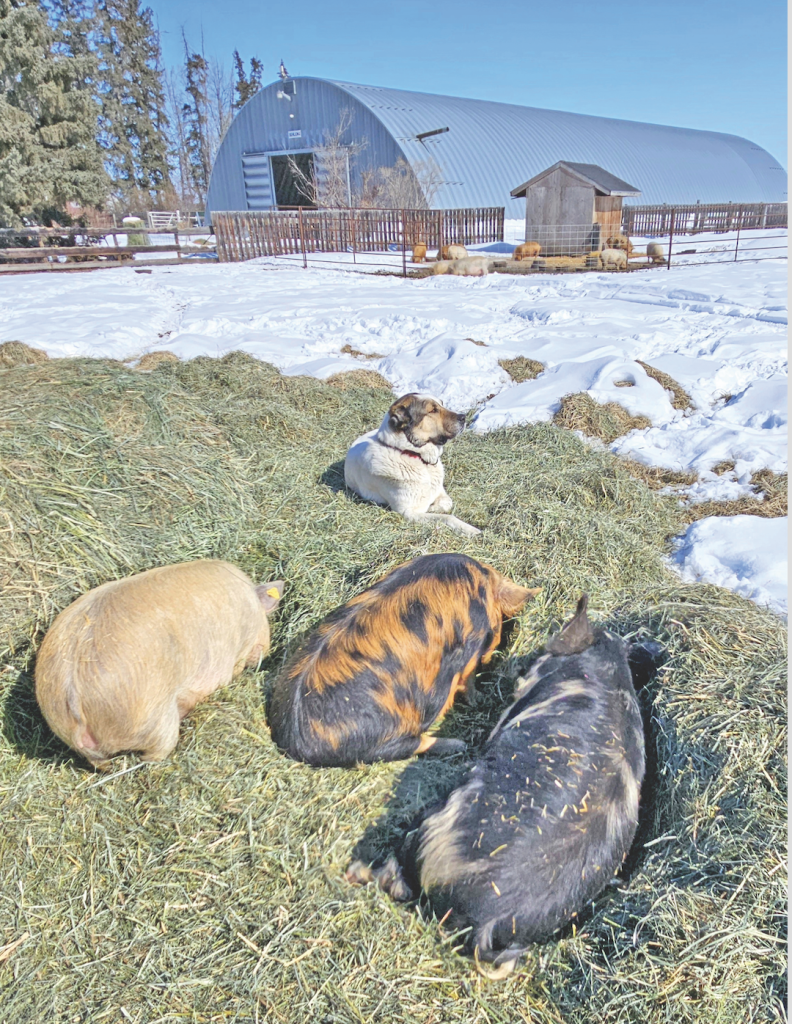

Kelly says coyotes have not been a problem so far. She and Jon have a guardian dog, Surlie, an Armenian Gampr that had been raised with pigs in Arizona. Surlie commonly takes her afternoon nap with the feeders and growers and hangs out at the barn door when she senses that a sow is about to farrow.

At this point, the farm is not quite self-sustaining, but it’s getting there, says Jon. Like all livestock producers, he and Kelly took a hard hit when the price of grain spiked, even though their hog ration provides only two and a half to three pounds of grain per animal per day.

Slower growing than commercial breeds, Kunes reach slaughter weight of 200 pounds at about 12 months. Kelly says the provincially inspected abattoir where she and Jon take their hogs was surprised at their size, anticipating that they would dress out to about 135 pounds. One female dressed out at 183 pounds.

Outcomes from the COVID pandemic and inflation have also devastated the slaughter industry, so that while there is still a selection of plants that will cut and wrap the carcasses, there are only two places left – one in Ponoka and another in Wetaskiwin – that will kill under provincial inspection, says Kelly.

Despite those challenges, the pigs are still twice as profitable as the cows, largely because they reproduce so much more quickly, says Jon. One of the first things he and Kelly learned when they ventured into raising beef was that there is a high price to be paid for overfeeding cows and for not selecting bulls with lower calf weights. It saves a lot of time and money if the animals are managed in a way that avoids the need for veterinary intervention, he says.

Kelly currently delivers meat to online customers in Calgary on Thursdays, and they work with a group that charges them a small fee to deliver to other points. Kelly is also looking at offering meat at farmers markets in Crossfield and Cochrane. She and Jon had set up at a Christmas market in Red Deer last year but found most of the people shopping there were looking for bargains rather than high-end pasture pork or grass fattened beef.

The couple attest to a steep growing curve since they purchased their first breeding stock from Tammy Keller at Ivanleigh.

Purchasing a bigger farm and expanding the operation took courage as well as a big investment.

Fortunately, they both had sufficient income. Jon works construction while Kelly had been a legal assistant. She left her job in December to work full time on the farm.

“We both worked pretty good jobs. Everybody else went on vacations and saved their money. We just decided to farm,” said Jon.

“We’ve got to be somewhat of an anomaly, doing farrow to finish on pasture pigs.”

Whispering Wind Farms can be viewed online at and by searching “whispering wind farms” on social media. •

— By Brenda Kossowan