The unnecessary loss of hundreds of weaner pigs after a transport truck rolled earlier this year has exposed a serious knowledge gap affecting anyone hauling livestock in Alberta. The push is now on to get that gap closed as quickly and tightly as possible.

In mid-spring, swine production manager Alastair Bratton was on a business trip to Calgary when he was asked to assist at the scene of a truck rollover near Standard, about an hour drive away.

A livestock truck hauling 2,250 isoweans to the United States had rolled. Some of the pigs were killed on impact. Others survived the crash, but were trapped in the trailer and could not be released for fear that they would run into traffic and cause further trouble.

Rescue equipment that might have helped Bratton save the surviving pigs was parked in a municipal storage lot, only an hour away. But Bratton didn’t know about Alberta’s network of livestock emergency trailers. Nor, it seems, did anyone else – including the 9-1-1 dispatch centre, where the information was supposed to be at the operators’ fingertips.

The surviving pigs died of heat and suffocation because they could not be removed from the trailer in time to save them, says Bratton. He believes they could have been saved if the nearest livestock emergency response trailer had been dispatched as soon as the initial call was made to 9-1-1, estimating that he and the trailer would have arrived at the scene at about the same time.

That is exactly what is supposed to happen any time there is an emergency involving livestock transport, says Cody McIntosh, agriculture services manager for Red Deer County.

In 2008, following discussion about the need for special equipment at collisions involving livestock, Red Deer County collaborated with Alberta Farm Animal Care to create the province’s first livestock emergency response trailer. The prototype, now maintained by the county’s emergency services department, carries portable corrals, ropes, halters, disposable coveralls, light plants, generators and a variety of other gear.

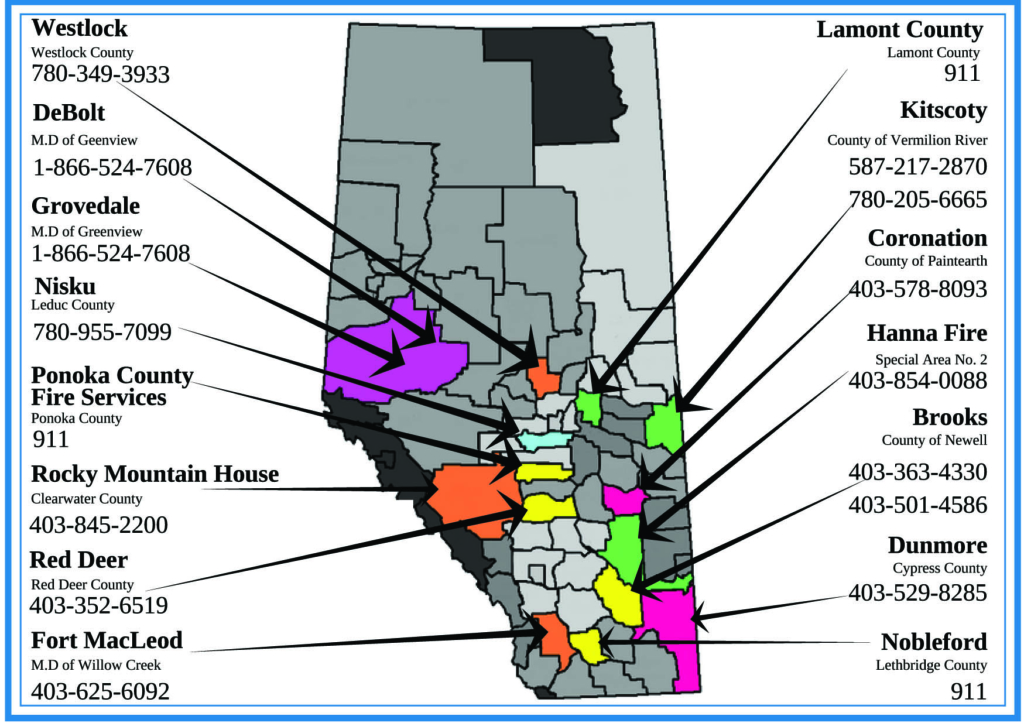

Ponoka County set up a similar trailer after the Red Deer trailer was launched. Other counties followed suit, creating what is now a network of 15 livestock emergency response trailers parked at strategic locations throughout the province. Their locations and contact information is supposed to be available to 9-1-1 dispatchers, along with AFAC’s 24-hour emergency ALERT line.

With Bratton’s encouragement, AFAC personnel are looking at why the system broke down and how to make sure that it works the way it is supposed to work the next time someone hauling livestock gets into trouble on the road – and every time after that.

But even in Red Deer County, where all first responders are trained for livestock emergencies and are aware of the trailer, there have been communication breakdowns in which it sat in the yard when it could have been put to use, says McIntosh.

The challenge now is for AFAC and its industry partners to get the word out and to make sure that everyone involved in livestock transport, including producers and truckers as well as first responders, knows how to find the nearest trailer, says Bratton.

In case the 9-1-1 dispatcher doesn’t have the information at hand, truckers and everyone else should have a copy of the postcard AFAC has produced showing where the trailers are located and giving the 24-hour contact numbers for them as well as the toll-free number for the ALERT line, says Brent Bushell, AFAC director and general manager of Western Hog Exchange.

In case the 9-1-1 dispatcher doesn’t have the information at hand, truckers and everyone else should have a copy of the postcard AFAC has produced showing where the trailers are located and giving the 24-hour contact numbers for them as well as the toll-free number for the ALERT line, says Brent Bushell, AFAC director and general manager of Western Hog Exchange.

Bushell says the board has not met since the rollover at Standard, but will discuss the incident at its next meeting. He has made a personal commitment to make sure everything possible is done to ensure that information about the trailers is as widely available and readily accessible as the trailers themselves.

Bushell suggested that all hauling units have a copy of the postcard in the cab and that it might also be helpful to have the 24-hour ALERT phone number posted on livestock trailers, in case the trucker is incapacitated.

While he and Bushell had not yet discussed the issue at press time, Bratton says he has been in touch with AFAC  staff. Kristen Hall, currently on maternity leave and former executive director Angela Greter had both been in touch with emergency dispatch centres since the rollover at Standard to remind them about the trailers and ensure that dispatch operators are using the information when needed.

staff. Kristen Hall, currently on maternity leave and former executive director Angela Greter had both been in touch with emergency dispatch centres since the rollover at Standard to remind them about the trailers and ensure that dispatch operators are using the information when needed.

Things would have worked out much differently for those little pigs if someone involved in the response had known that a specialized response unit was available, says Bratton. He hopes the incident will help raise awareness throughout the livestock industry so that a well-intentioned program can be put to work as it was designed.

Please refer to the AFAC postcard as published in this issue of Prairie Hog Country for the ALERT number as well as site locations and contact numbers for the trailers. •

— By Brenda Kossowan